Marianne Bjørnmyr

Shadows / Echoes II

All Images © Marianne Bjørnmyr

|

“We see the things themselves, the world is what we see: formulae of this kind express a faith common to the natural man and the philosopher – the moment he opens his eyes; they refer to a deep seated set of mute “opinions” implicated in our lives. But what is strange about this faith is that, if we seek to articulate it into theses or statements, if we ask ourselves what is this we, what seeing is and what thing or world is, we enter into a labyrinth of difficulties and contradictions.” Maurice Merleau-Ponty, beginning of The Visible and the Invisible, translated by Alphonso Lingis.

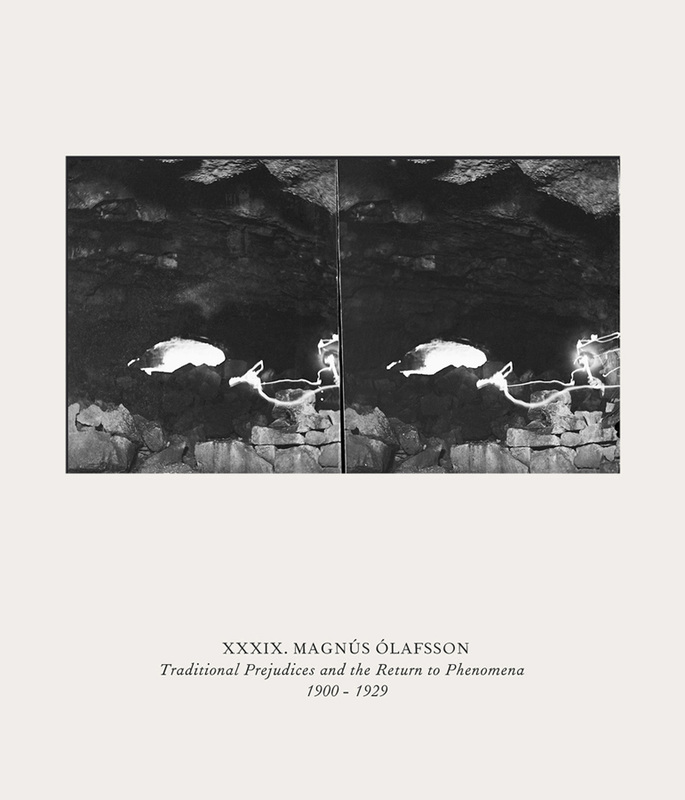

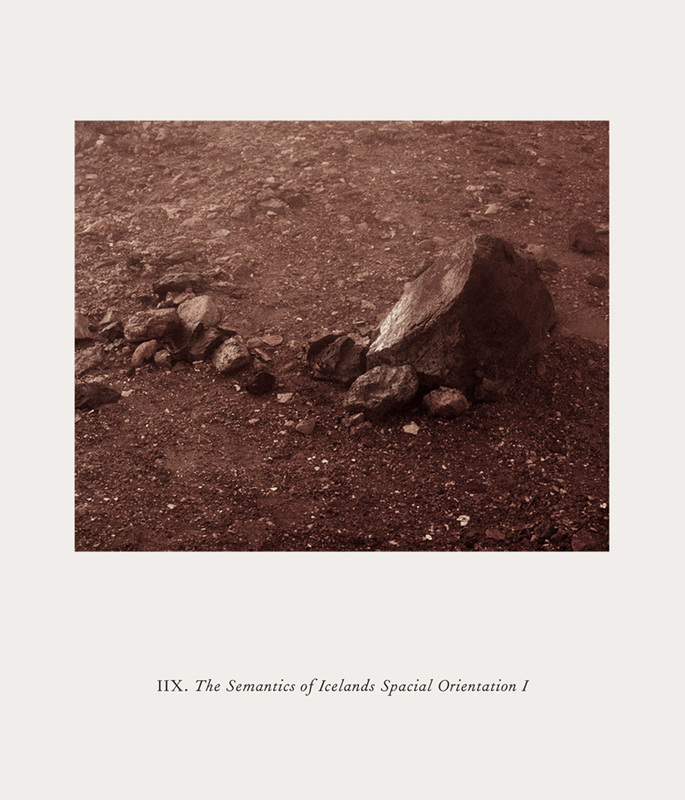

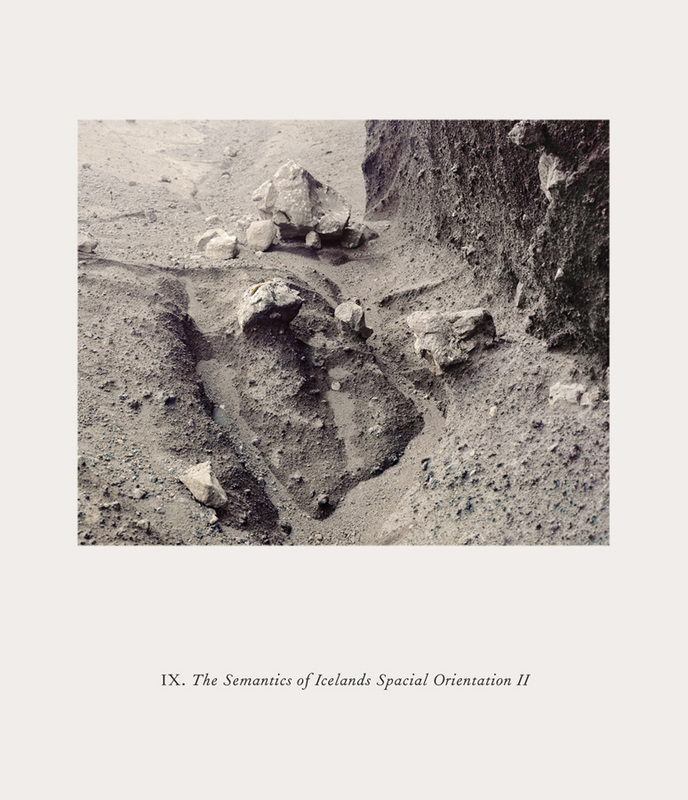

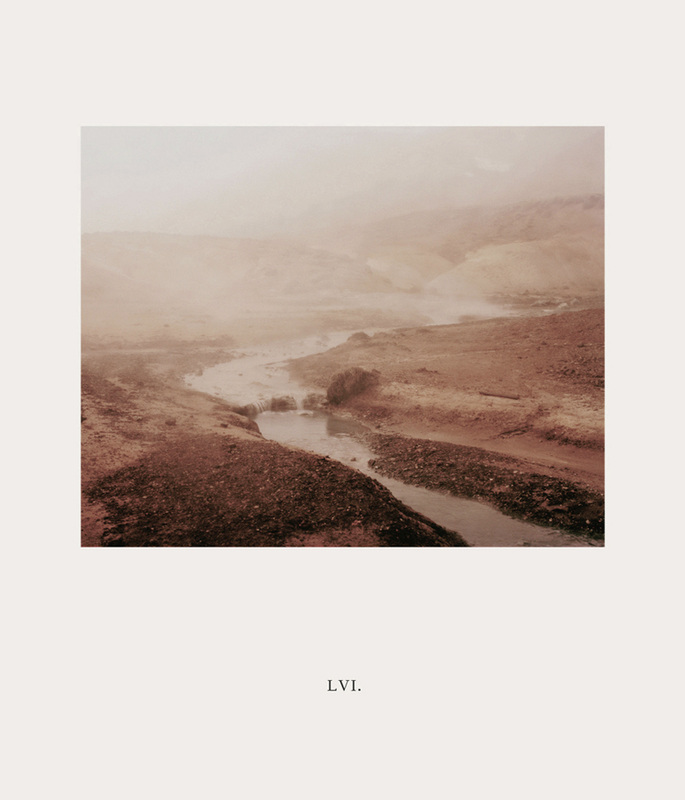

In her photography book Shadows/Echoes II, Marianne Bjørnmyr presents a selection of images and words that she seems to have crafted and foraged rather than made or taken. She shows the real and the imaginary through fumes, hues of copper and grey, and flashes of light. On several of her photographs, she captures Iceland’s dry soils with a semblance of scientific endeavour that brings a twist to traditional landscape photography. Many of her images seem to witness the transition from rock to dust, a process which fits the theme outlined in the key accompanying text: the “in-between-time”. Whether or not she succeeds in capturing what she set out for – the essence of elves and fairies – she definitely is successful in exploring the ephemeral and transitory, be it subtle dusk and dawn lights or the transient fog. In the delicate detail of a rock, cropped in a tight circle, you can see all the cracks, feel the rugged texture and witness the passage from one colour to another. In other pictures, devoid of any horizon, you find yourself once again robbed of any contextual information or sense of scale. You are left to revel in a monochromatic tableau where texture and light combine to create a sculptural apology of the mineral. Marianne has also included in her work black and white stereoscopic photographs that she found. She presents them on an equal footing with her own photographs, thus blurring the divide between creation and appropriation. This fully contributes to her overall undertaking of building bridges between the real and the unreal. Stereoscopic images have the specificity of being doubled and taken from a slightly different angle in order to reproduce 3D vision. Marianne’s contemporary use of these images, which are here deprived of their original context and whose iconography is further obscured by captions taken from Merleau-Ponty’s philosophical treaties, is particularly clever. The overall uncanny dimension of the book is heightened by these objects coming from a past we struggle to relate to anymore. |

This difficulty to relate is exactly what is at play in this book: Marianne went and sought Icelandic traditions and beliefs that we (as rational modern viewers) may find foreign and remote, and she tried to understand them from the inside. The text “Extract From Conversation” is what makes the whole story come to life and helps you enter this magic world. You then try to see fairies and elves for yourself. Fog becomes laden with spirits; light effects now have a meaning.

The scattered quotations by twentieth century philosopher Merleau-Ponty further bind the alchemy, as they are paradoxically used to both illuminate and obscure the story. His philosophy of phenomenology takes as a starting point “phenomena”, that is to say everything that we can access through our senses. Elves and fairies definitely elude man’s senses, however, and interestingly enough, in this case the camera takes the place of the human eye. At least for Marianne’s character and amateur photographer Ragnhildur Jonsdottir, the camera acts as witness of their presence. But capturing their fleeting existence still remains difficult and given only to “clairvoyants” (could this be a metaphor for the figure of the traditional artist-genius?). Merleau-Ponty’s sentences back up what we, as viewers, may think: that perceiving fairies is part of an obscurantist belief, that they are “traditional prejudices”, at best a doubtful supernatural “phenomenon” (note here the play on this word). But Merleau-Ponty’s expressions are further used as poetic rather than signifying instances. “The perceptual Faith and Its Obscurity” and “Traditional Prejudices and the Return to Phenomena” (both excerpts from The Visible and the Invisible) slowly lose their philosophical pregnancy. They become fragmentary accompaniments to the stereoscopic images, in a way that goes beyond rationality to enter the sphere of sound and poetry, a sphere where seeing fairies is plausible. Erica Payet |

Marianne Bjørnmyr |

Erica Payet |

|

Marianne Bjørnmyr is a Norwegian artist, living and working in London. Marianne completed a MA in Photography at London College of Communication in 2012. Her photographic practice revolves around our perception of the photograph's relation to reality. Through her research she explores the phenomena of myth, and how the photograph’s role in conveying objects and surroundings is set up against our understanding, interpretation and generated perception of imagery.

Marianne’s work has been exhibited at numerous galleries including Foto8 Gallery, The Royal Shakespeare Company and AOP Gallery. She has been awarded the Daniel Blau 5 under 30 Prize and First Prize at Juvenarte, the School of Arts price for Photography at Roehampton University. www.mariannebjornmyr.com |

Erica Payet studied History of Art, with a focus on the History of Photography, at the Ecole du Louvre in Paris. Also a graduate of the Sorbonne in Paris and King’s College London, she has been working at Daniel Blau photography gallery in London for nearly two years. Her photography exhibitions reviews can be read on her blog, Watching Photographs. She was the runner-up for the Breese Little Prize for Art Criticism Vol. VIII in 2013.

watchingphotographs |